Open Access, Volume 9

Qualitative review of treatment for extrarenal angiomyolipomas

Kavya Rao1*; Vijay Singh2

1Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York, USA.

2Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, Northwell Health, USA.

Kavya Rao

Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York, USA.

Email: krao1@pride.hofstra.edu

Received : January 02, 2023

Accepted : February 01, 2023

Published : February 10, 2023,

Archived : www.jclinmedcasereports.com

Abstract

Angiolipomas are a form of lipoma that are characterized by all features of a typical lipoma and may also contain a vascular component. These benign growths typically form subcutaneously in the extremities, trunk, neck, and head [1]. Similar to angiolipomas, angiomyolipomas are another classification of a benign growth, which has a muscle tissue component along with the adipose tissue and vascularity within the growth. Angiomyolipomas typically form in the kidneys [3]. It has been established that both angiolipomas and angiomyolipomas are distinct in that they are found in common, respective regions of the body. There are instances, however, when angiolipomas and angiomyolipomas form in other areas of the body- namely in the internal organs or along the visceral walls of the torso or mouth. Here, we report an exceptionally rare case in which a pulmonary angiomyolipoma was discovered in the lung of a patient. Extrarenal angiomyolipomas have rarely been found to form in the lungs [3]. We have reviewed the few cases of angiomyolipoma in the lungs and an assessment was made in order to better understand the extrarenal formation of this particular pulmonary growth.

Keywords: Angiomyolipomas; Extrarenal; VATS; Pulmonary

Abbreviations: VATS: Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Medications; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CT: Computed Tomography; FSA: Frozen Section Analysis; AP: Anteroposterior; RERAML: Retroperitoneal Extrarenal Angiomyolipomas; SMA: Smooth Muscle Antibody; SMM: Smoldering Multiple Myeloma; MDM2: Mouse Double Minute 2

Copy right Statement: Content published in the journal follows Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). © Rao K (2023)

Journal: Open Journal of Clinical and Medical Case Reports is an international, open access, peer reviewed Journal mainly focused exclusively on the medical and clinical case reports.

Citation: Rao K, Singh V. Qualitative review of treatment for extrarenal angiomyolipomas. Open J Clin Med Case Rep. 2023; 1975.

Introduction

Angiolipomas are a form of lipoma that are characterized by all features of a typical lipoma and may contain a vascular component. These benign growths typically form subcutaneously in the extremities, trunk, neck, and head and include those that form internally on the visceral walls of the torso, and in or near certain organs, such as the kidneys [1]. There are two kinds of angiolipomas, each categorized by the extent of growth- non-infiltrating and infiltrating angiolipomas [2]. Non-infiltrating angiolipomas are more common and do not extend deep into the skin, while infiltrating angiolipomas extend deeper into the skin and either muscle, fat, or fibrous tissues [2]. Angiolipomas constitute approximately 5% to 17% of lipomas [2]. Angiolipomas that cause pain or discomfort are often surgically removed from patients as a line of treatment [2]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) may also be given to afflicted patients to reduce any pain felt due to angiolipomas.

A similar type of benign growth to angiolipoma is angiomyolipoma, which contains muscle tissue, adipose tissue, and vascular components to their growth. Most commonly, angiomyolipomas are found in the kidney, and thus are referred to as renal angiomyolipomas [2,3]. Treatment often entails active surveillance to monitor the growth and changes in small and painless angiomyolipomas. Additionally, mTOR inhibitors or surgery may be recommended if the tumor causes symptoms or presents to be cancerous [4].

Lipomas are typically benign mesenchymal tumors that originate from mature adipocytes. Incidence of lipomas are generally found in the head, neck, torso, and extremities and form subcutaneously. When identifying lesions, any deviations of lipomas from other variants, such as angiolipoma and angiomyolipoma, are found through MRI, CT, sonography, and aspiration biopsy [5]. The most definitive diagnosis for lipoma in most literature has been by use of histopathology [5].

Here, we report an exceptionally rare case in which a pulmonary angiomyolipoma was discovered in the lung of a patient. Extrarenal angiomyolipomas have rarely been found to form in the lungs [6]. We have reviewed the few cases of angiomyolipoma in the lungs and an assessment was made in order to better understand the extrarenal formation of the pulmonary growth.

Case Presentation

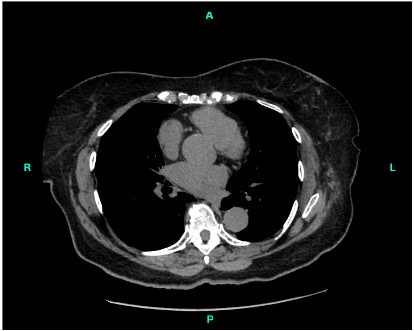

An 82-year-old female was found to have a growth located in the anterior lobe of the left lung, which was later identified as an angiomyolipoma (Figure 1). Clinical history of the patient revealed the growth to be a slow-growing left lower nodule.

Investigations and Treatment

The patient underwent Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) intervention as a treatment for the angiomyolipoma; specifically, a wedge resection of the left lower lobe of the lung was performed. The size of the resected growth was consistent with an angiomyolipoma of the lung, measuring approximately 1.4 centimeters in diameter. The tumor appeared well demarcated and partially encapsulated and was composed of mixed mesenchymal elements- myoepithelial cells and adipose tissue, with a very low proliferative index (ki67) and without pleomorphism. Additionally, clinical or imaging correlations had been recommended for an official diagnosis.

The resected specimen consisted of a 38.5 g, 8.5 x 8.0 x 2.7 cm3 triangular wedge of lung tissue. The pleura was purple, smooth, and glistening, and a 1.4 x 1.1 cm2 area was incised and designated with a stitch marking a nodule, located 1 centimeter from the staple line. A representative section of the nodular area was submitted for Frozen Section Analysis (FSA). The pleura surrounding the nodule was inked blue. The staple line was removed, and the underlying parenchyma was inked black. Section reveals a 1.3 x 1.3 x 1.2 cm3 firm, white nodule focally coming within 0.1 cm of the pleura and within 0.5 cm of the staple line. The remaining cut surfaces display tan, spongy to slightly firm and congested parenchyma. No other masses were grossly identified. The entire nodule and representative sections were submitted in nine cassettes.

Immunostains were performed on the resected tumor, which tested positive for HMB45, actin, melanA, Smooth Muscle Antibody (SMA), S100, and Smoldering Multiple Myeloma (SMM) and tested negative for Mouse Double Minute 2 (MDM2), CkAE1/AE#, CD117, beta Catenin, Alk1, p63, CD34, ki67-1%, and Desmin. The controls for the immunostains were noted as appropriate.

Outcomes and Follow Up

Noncontrast Computed Tomography (CT) scans of the chest were first obtained after the surgical VATS procedure. The central tracheobronchial tree was patent and, in comparison to previous CT scans approximately three and half years prior, there was an unchanged 4 millimeter nodular opacity along the right minor fissure. The scans showed partial left lobe resection with associated postsurgical changes in mild soft tissue. These changes were difficult to evaluate as it was the first postsurgical CT scan and may more likely represent post-surgical change rather than the recurrence of disease.

Portable chest radiograph Anterior-Posterior (AP) view of the chest was obtained one day post-VATS and was compared to a chest radiograph of the patient from six and a half years prior and the CT chest scan from the day prior. Status post right lower lobe nodule resection radiograph showed surgical sutures in the operative site of the left infrahilar parenchyma, the left chest tube tip overlying the medial left upper henithorax, and no extra pleural air or fluid collection. Additionally, the base of the right lung showed linear chronic discoid atelectasis secondary to elevated right hemidiaphragm, eventration of the diaphragm, and thickening of the right minor fissure. The osseous structures were visualized to be intact. These findings were observed the following day from a portable AP view chest radiograph.

Single frontal view chest radiography was obtained three days post VATS operation. The patient was unable to communicate and was short of breath. The lungs demonstrate the left-sided chest tube in place. A small left apical pneumothorax was seen, and subcutaneous emphysematous changes were seen along the left lateral chest wall region. The right lung field appears clear of infiltrate or effusion. The heart and mediastinum appear intact.

Chest X-Rays after the removal of the chest tube from a single AP view were taken and compared to Chest X-Rays taken prior to the interval removal of the chest tube. Subcutaneous emphysema and a small left apical pneumothorax were seen again. Additionally, there was linear atelectasis or scarring was noted at the right lung base and opacity at the left lung base was observed and noted to likely be atelectasis. The heart size remained normal and degenerative changes were noted in the spine. The small left apical pneumothorax had not significantly changed since the last chest X-Ray one day prior. Additionally, non-contrast axial multidetector CT scans of the chest were taken from lung apices to lung bases four months after the VATS procedure (Figure 2). The left lower lung lesion from prior study had been removed and surgical clips and scarring were identified in the images.

Once removed, tissue from the left lower lobe nodule was tested for fungal cultures and with a gram stain. No fungus was isolated from the tissue culture at one and two weeks. The culture tissue with the gram stain showed no growth at four days, with few white blood cells and no observations of organisms.

Discussion

Currently, the exact pathogenesis and specific causes of angiolipomas remain to be elucidated. However, hypotheses about the initiation of these growths include the long-term use of corticosteroids, diabetes, genetics, and post-hormonal reactions, as there is a greater incidence of angiolipomas in individuals between the ages of 20-30, and in response to minor, repetitive injuries [2]. Additionally, angiolipomas are commonly found in areas subject to irritation and acute trauma, which is hypothesized to act as a possible etiologic factor as the adipose cells will incorrectly proliferate and result in growth. Extended stimuli such as extended acute trauma may cause a vascular component to integrate into the lesion, as well. In contrast, the cause of renal angiomyolipoma has been attributed to mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 genes, which act as tumor suppressor genes and produce the tuberin protein [4].

Despite the typical presentation of angiolipomas and renal angiomyolipomas, there are seldom instances in which they are found in other areas of the body, namely in the internal organs or along the visceral walls of the torso or mouth. Angiomyolipomas, which are found outside the kidneys, are classified as extrarenal angiomyolipoma and have been reported to be found in several organs such as the liver, reproductive organs, skin, and retroperitoneum [6]. In these instances, additional measures are utilized to ensure proper diagnosis. Often, extrarenal angiomyolipomas present as incidentalomas while screening for other pathologies [7].

In the case of Retroperitoneal Extrarenal Angiomyolipomas (RERAML), imaging and histopathology results are similar to those of retroperitoneal liposarcomas. However, specific findings, such as dilated intratumoral vessels and absence of calcifications, can lead to proper diagnosis and thus, proper, noninvasive treatment and surveillance [8]. As of 2018, only 60 cases of extrarenal angiomyolipomas had been reported, the majority of which were found in the liver or the retroperitoneum [9]. Cross-examination of the literature identified one other instance of an angiomyolipoma found in the lung [10]. According to Marciex et al, the patient was a 63-year-old female with no report of ailment that would cause the growth otherwise [10]. Thus, our particularly rare case of extrarenal angiomyolipoma, especially in the lung, presents an opportunity to understand how to diagnose and treat atypical clinical presentations of angiomyolipoma.

Declarations

Guarantor Statement: VS had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author Contributions: VS had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. VS contributed substantially to the study design, interpretation, and KR contributed substantially to the writing of the manuscript. VS contributed substantially to the study design and statistical analyses.

Financial/nonfinancial Disclosures: We have no funding information to disclose.

Patient Consent Statement: Proper consent from the patient described in this case study was obtained. Due to the rarity of the case presented, personal patient information has been kept separate from any medical results and images in this case study.

References

- William J, Timothy B, Dirk E. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 2005.

- Cleveland Clinic. “Angiolipoma: Symptoms, Causes and Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 2021.

- Morgan, Matt A.; Amini, Behrang (2020 revised) ‘Renal angiomyolipoma’.

- Cleveland Clinic. “Renal Angiomyolipoma: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 2022.

- Ruchi B, Priyanka D, Fakir DM, Sanat Kumar B. Non-Infiltrating Angiolipoma of Floor of Mouth-A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. 2017.

- Ito M, Sugamura Y, Ikari H, Sekine I. Angiomyolipoma of the lung. 1998.

- Minja E, Pellerin M, Saviano N, Chamberlain R. “Retroperitoneal Extrarenal Angiomyolipomas: An Evidence-Based Approach to a Rare Clinical Entity.” Hindawi, 2012.

- Anugayathri J, Joao KT. Retroperitoneal extrarenal angiomyolipoma at the surgical bed 8 years after a renal angiomyolipoma nephrectomy: A case report and review of literature. Urology Annals. 2017; 3: 288-292.

- Wroclawski ML, Baccaglini W, Pazeto CL, Carbajo C, Matushita C, et al. Extrarenal Angiomyolipoma: differential diagnosis of retroperitoneal masses. Int Braz J Urol. 2018; 44: 639-641.

- Marcheix B, Brouchet L, Lamarche Y, Renaud C, Gomez-Brouchet A, et al. Pulmonary Angiomyolipoma. 2006.